|

|

"Honky Tonk Visions"

by Elizabeth

Skidmore Sasser

Why do music and art flourish

on the flat cotton patch of the South Plains?  Butch

Hancock, described as one of the best songwriters in America

in the folk-poet tradition, and who is also a photographer and

former architecture student, replies with an answer that is as

good as any. He explains that "all of the winds from the

North Pole come across Kansas until they hit the Yellow House

Canyon and then they spill out in every direction sending all

of the ideas for music [and art] swirling around.' Paul

Milosevich, in the 1970s, was

in the right place at the right time to be blown about by the

blue northers into a head-on collision with a remarkable group

of young musicians, many of whom were also writers and artists. Butch

Hancock, described as one of the best songwriters in America

in the folk-poet tradition, and who is also a photographer and

former architecture student, replies with an answer that is as

good as any. He explains that "all of the winds from the

North Pole come across Kansas until they hit the Yellow House

Canyon and then they spill out in every direction sending all

of the ideas for music [and art] swirling around.' Paul

Milosevich, in the 1970s, was

in the right place at the right time to be blown about by the

blue northers into a head-on collision with a remarkable group

of young musicians, many of whom were also writers and artists.

…One of the few night spots for

dancing in Lubbock during the fifties and sixties was the Cotton

Club. The club’s later days (in the late

seventies) were associated with Tommy

Hancock, billed (among many titles) as Tommy

Hancock and the Supernatural Family Band. Hancock

is referred to affectionately as "Lubbock's

original hippie." The no-longer-existent dance

hall was commemorated by Milosevich with a watercolor of the

old sign left standing to blow in the wind above the bare ground.…

…One of the few night spots for

dancing in Lubbock during the fifties and sixties was the Cotton

Club. The club’s later days (in the late

seventies) were associated with Tommy

Hancock, billed (among many titles) as Tommy

Hancock and the Supernatural Family Band. Hancock

is referred to affectionately as "Lubbock's

original hippie." The no-longer-existent dance

hall was commemorated by Milosevich with a watercolor of the

old sign left standing to blow in the wind above the bare ground.…

For decades, Lubbock, the self styled "Hub

of the Plains" drew musicians to its center;

these musicians then fanned out over the country watching the

cotton gins disappear in their rearview mirrors. The early generation

included such names as Plainview singer Jimmy Dean, the late

Roy Orbison from Wink, producer Norman Petty from Clovis, Texas

Tech architectural student John Deutchendorf -- better known

as John Denver, Littlefield's Waylon Jennings, Mac Davis, and

many others. The list comes full circle with the mention of that

founding father of rock 'n roll, Buddy Holly and the Crickets.

It is with the new generation, however,

that this chapter is concerned. This goes back directly to the Flatlanders, a Lubbock band of

the early 1970s that brought together Butch

Hancock, Jimmie Dale Gilmore,

Tony Pearson, and Joe Ely. Other well -knowns include

Ponti Bone, Davis

McClarty, Jesse Taylor,

who are, or  were, members

of Ely's band. were, members

of Ely's band.

The roster continues with the Maines

Brothers, the Nelsons,

Jim Eppler, who was often

painted and sketched by his friend Milosevich, Terry

Allen, as well known as an artist as a musician, and

Jo Harvey Allen, actress

and writer.

The time was ripe not only for new sounds and rhythms but also

for Milosevich’s West Texas realism

and its empathy with the obvious and the overlooked.

It carried the right message and created a link between the painter

and the music people. Milosevich says he met Joe Ely "officially"

at Fat Dawg's and

[I listened] to his music at the

Cotton Club, Main Street Saloon;  wherever he and his band played I was there

with a sketch pad. I did Joe’s first album cover, a charcoal

portrait. [I] began it about 8 in the morning, and he took it

to California that afternoon. The original got lost out there,

but we were fortunate to have taken good photos of it and made

prints.… wherever he and his band played I was there

with a sketch pad. I did Joe’s first album cover, a charcoal

portrait. [I] began it about 8 in the morning, and he took it

to California that afternoon. The original got lost out there,

but we were fortunate to have taken good photos of it and made

prints.…

Recalling another encounter, Milosevich says, "I met Terry

Allen over the phone." The story goes like this: Terry Allen

and Jo Harvey graduated from Monterey High School

in the Hub City and were married. They left the South Plains

as quickly as possible, heading for the West Coast. 'Terry said

in an interview, "I convinced myself when I was growing

up that I hated Lubbock; I made it a scapegoat for everything

that was wrong. . . You never see your hometown until you go

away" School

in the Hub City and were married. They left the South Plains

as quickly as possible, heading for the West Coast. 'Terry said

in an interview, "I convinced myself when I was growing

up that I hated Lubbock; I made it a scapegoat for everything

that was wrong. . . You never see your hometown until you go

away"

It was during a holiday visit to Lubbock that Allen received

the call from Milosevich. The artist had heard that Allen was

in the process of recording some new material and suggested to

Terry that he might want to get in touch with Joe Ely, Lloyd Maines,

and the Caldwell Recording Studio while he was in

town. Later, Allen told Milosevich that he drove around the block

a hundred times trying to make up his mind what to do. He didn’t

want anything to do with Lubbock, but he had a hunch that he

should follow up on Paul's suggestion. The result was the two-record

set Lubbock:

on Everything.

Terry Allen’s attitude towards Lubbock has changed in

the last few years. He admits:

There is something about West Texas

that gets stuck in the bones. That something is never felt stronger

than when a native is several thousand miles from home. Maybe

a chip was planted long before cowchips were outmoded by the

computer. The tendency is for West Texans who develop a case

of nostalgia to come loping home by air or pickup. You go back,

exasperating as it may seem, because you want to go back and

you know damn well there's nothing there except your memories

and your friends and the flat land and the wind; that's enough.

It makes you know who you are and stiffens your back for going

away again.…

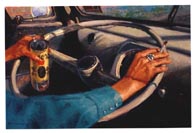

Terry Allen’s song "Amarillo Highway" leads south to

Lubbock. Terry says that as long as it's possible to get out

in a car on a starlit night, on a straight road with the radio

turned up high, no one should ever need a psychiatrist.

Butch Hancock's

poetry bites through the dryness and unbroken bowl of the sky

to speak up for dirt roads and cattle guards, for trucks and

tractors: Butch Hancock's

poetry bites through the dryness and unbroken bowl of the sky

to speak up for dirt roads and cattle guards, for trucks and

tractors:

This old road is hard as pavement.

Tractors and trailers have sure packed it down,

There's deep ruts and big bumps

from here to the city.

This old road's tough but it sure gets around.

Trucks, pickups, cars, and the sun overhead are signs and

symbols that set wheels in motion and circles spinning. One of

Butch's songs says, "This old world

spins like a minor miracle." Woody Guthrie's

"Car Car Song" is one of the "modern lullabies"

Ely has recently recorded for his daughter. It is no mystery

why David

Byrne chose to open and end the film True Stories with frames of a red

convertible parked on a road that stretched from nowhere to nowhere.

Both beginning and ending are left open ended to reach out to

infinity: "Enlightenment doesn’t care how you get there!"

...Another [Paul] Milosevich painting, this time of a truck,

was a pivotal point of an exhibition hosted in the fall of 1984

by The Museum, Texas Tech University. Future Akins, interim curator

of art, was one of the forces behind the idea of bringing together

artists and musicians in an unexpected three-dimensional, multimedia,

foot stompin’ tribute to West Texas music.…

[Milosevich] painted a West Texas ranch hand sitting in the back

of a pickup and strumming a guitar. Its title, Nothin'Else

to Do, became the name given to the exhibition.

During the ‘fifties and ‘sixties in Lubbock, "nothin’

else to do' meant hangin’ out at the Hi-de-Ho

Drive-in, listenin’ to the radio, or gettin’

together with like-minded friends to do some pickin’ on

the guitar or banjo, playin’ the harmonica or maybe the

saw or washboard, perhaps formin’ a jug band.

An eloquent tribute to Milosevich's painting was written by Mikal

Gilmore:

For me, one of the more memorable

depictions of [the] push-pull between freedom and flight (the

tension at the heart of so much West Texas music) was... a painting

by Paul Milosevich of a young cowhand sitting on the rear end

of a pickup ...

a

look of intense yearning on his face as he stares over the illimitable

Texas flatlands... dreaming a way out of his fateful indolence.

Stationed just in front of the painting was an honest-to-goodness

1957 salmon pink Cadillac with charcoal blue upholstery ... Taken

together, the painting and the car told a timeless, virtually

mythic story of longing and attainment. a

look of intense yearning on his face as he stares over the illimitable

Texas flatlands... dreaming a way out of his fateful indolence.

Stationed just in front of the painting was an honest-to-goodness

1957 salmon pink Cadillac with charcoal blue upholstery ... Taken

together, the painting and the car told a timeless, virtually

mythic story of longing and attainment.

The Cadillac's pink fins pointed towards the heart of the

exhibition, a tribute to C.B. Stubblefield

of the famous Stubb’s

BBQ, and another of Milosevich's friends. From

1969, when the small place on East Broadway was opened, it was

a haven to almost every musician worth his beer, whether from

Lubbock or just passing through. Stubb's Sunday

Night Jam Sessions offered a platform, a bit cramped

in size but big in soul, to those on their way up and those on

their way down. A musician could always count on Stubb's words

of encouragement offered with humor and hot ribs and cold beer.

A few years ago, when Stubblefield was  approached

by the Internal Revenue Service, rumor has it, he responded to

their charges of failure to file income tax returns with the

severe logic, "I never made any money, why should I pay

taxes?" approached

by the Internal Revenue Service, rumor has it, he responded to

their charges of failure to file income tax returns with the

severe logic, "I never made any money, why should I pay

taxes?"

One of the legendary events that took place at Stubb's will

challenge generations of folklorists. This is The

Great East Broadway Onion Championship of 1978.

It inspired a Tom T. Hall song by the same name which

appeared in the album, Places Where I've Done Time. It

was also the subject of a black-and-white painting by Milosevich

and Jim Eppler. According to the painter, it all began one evening

when Hall, Paul, Jim Eppler, and "a guy named Al" were

sitting around drinking beer and talking. Hall had never met

Stubb; to remedy this they drove out to East Broadway. When they

got there, Joe Ely was shooting pool in the back room, and before

anyone could say "eight ball," Tom T was in the game.

"Smoke was hangin’ low and thick"; as play accelerated,

it got hotter and hotter, and later and later. Joe's girl friend

Sharon, who is now his wife,

was tired and disgusted, so she pounced on the cue ball and carried

it off. Refusing to be discouraged, Ely reached into a bag of

Stubb's onions, took out a big one, and put it down on the felt

to the disbelief of the kibitzers standing around roaring with

laughter. He announced that he was going to play with a broom

handle, which he did. Milosevich explains that this "cue

stick" really sliced up and punctured an onion  pretty

badly, which meant that the onion had to be replaced from time

to time. When the game ended, the table looked like a green hamburger

covered with chopped onions before the catsup is added. Tears

were streaming from the competitors' eyes as they battled on,

until finally Tom T. was declared the winner of the championship

title. Magnanimously, Joe Ely offered a rematch the following

year, but Hall said, "No. There are a lot of good onion

players out there, and they deserve a shot at the title, too'

" In Milosevich's and Eppler's painting, Tom is grinning

on the left. Ely is easily identifiable by the broomstick he

holds. In the background, Jim Eppler and the painter, drinking

beer, are back to back with profiles facing in opposite directions

like the Roman god Janus. pretty

badly, which meant that the onion had to be replaced from time

to time. When the game ended, the table looked like a green hamburger

covered with chopped onions before the catsup is added. Tears

were streaming from the competitors' eyes as they battled on,

until finally Tom T. was declared the winner of the championship

title. Magnanimously, Joe Ely offered a rematch the following

year, but Hall said, "No. There are a lot of good onion

players out there, and they deserve a shot at the title, too'

" In Milosevich's and Eppler's painting, Tom is grinning

on the left. Ely is easily identifiable by the broomstick he

holds. In the background, Jim Eppler and the painter, drinking

beer, are back to back with profiles facing in opposite directions

like the Roman god Janus.

In 1984, when Stubblefield locked the door of his barbeque

parlor for the last time before moving to Austin, Future Akins

and Clyde Jones, the University Museum director, were on hand

to salvage as much of the history-making memorabilia as possible

and to organize the mementoes into a three-dimensional display

for the Nothin’ Else to Do exhibition. The tribute to Stubb

occupied a display area where the booths and posters were arranged.

Gazing down upon the old piano was a deer's head, glass eyes

staring through dark glasses. Hanging on a wall, the famous sign

announced "There will be no BAD talk or LOUD talk in this

PLACE," and another

placard carried the instructions "Equal

time for all musicians. No more than 2 guitars at a time. Thank

You."

Milosevich says, "Now on East Broadway, where Stubb's little

joint was, there's just a bare concrete slab with a lot of good

vibes still hovering above it. Recently, Stubb stood on that

slab, looking around East Broadway, and then returned his gaze

to the bare concrete. He laughed, "It's like looking at

the bottom of a good cup of coffee!"

Nothin’ Else to Do helped

pave the way for the Texas Tech Museum’s response to the

state's sesquicentennial anniversary in 1986. Gary Edson, Museum

director, and Future Akins, at that time curator of art, planned

an unusual recognition of the musicians and artists who had tapped

the vital forces of the South Plains. A review of the exhibition

in Artspace Magazine describes that background:

In the last decade, chunks of Texas

have been seized by metroplexamania and stamped by the boots

of office cowboys working-out on mechanical bulls. Driving along

West Texas roads, however, a nostalgia for simpler times is still

stirred by songs drifting from jukeboxes in cafes and truck stops.

The songs wail with memories of warm hearts, cold lips, 90 proof

whiskey, and unrequited love. The neon glowing in the blackness,

the music, and rubbin’ elbows inspired Honky Tonk Visions.

Honky Tonk Visions

invited live performances by musicians and art inspired by the

honky-tonk theme. Among those participating, Terry Allen built

a three-dimensional environment that was a tribute to old friends

and memories.

A white wooden bed was the focal point. All over the amorous

piece of furniture there were words from favorite love songs

inscribed in multicolored paints and markers by Lubbock musicians

and high school buddies. The museum staff gasped one afternoon

to see members of the Maines Brothers

Band piling from their bus and running into the gallery

so each could write a few lines. ... On the night that Honky

Tonk Visions opened, the bed was suspended within a room enclosed

by solid walls on two sides and a screen mesh defining the remaining

side. Pierced by emotions, the bed was penetrated by knives,

swords, hatchets, and machetes. . . Every ill-fated lover suffering

from love, deserted by love, abandoned in the mournful words

of country and western music, once slept here...

Return to

Stories or Home

|